Size: large

Type: image

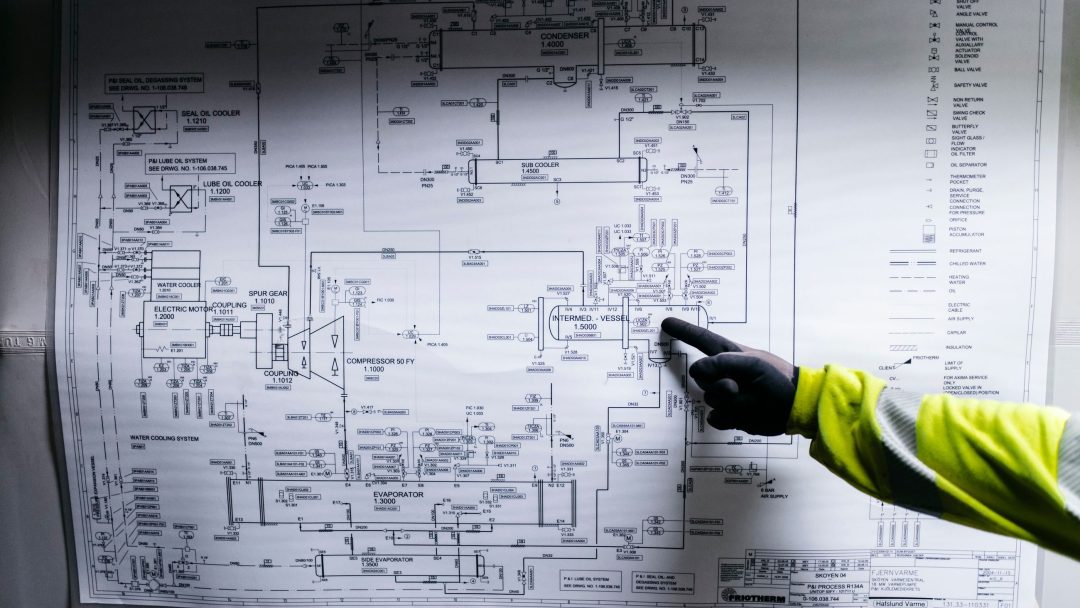

In an unobtrusive location in the heart of a residential area in Oslo’s Skøyen district, we find one of Fortum Oslo Varme’s district-heating plants. The plant is far larger than at first appears. Three-hundred metres inside the rockface there are sewage pools and a large pump forcing 3,800 m3of sewage per hour through two enormous heat pumps. The pumps extract heat from the sewage. This year they supplied the city with enough district heating for 13,000 apartments.

Cheap district heating

Inside the plant we meet operating technician Per Ivar Bergseth. He is responsible for the day-to-day running of the Skøyen plant. He also monitors plants at Rodeløkka, Økern and Tokerud.

“This is one of our cheapest and most eco-friendly plants, and accordingly it’s also the most important plant under my supervision,” says Per Ivar, who hands out protective clothing and equipment, before we enter the tunnel leading to the plant. Usually Per Ivar rides his bicycle to complete his daily round of inspections – a task that involves nearly all his senses.

- provides approx. 20 % of heating requirement (25 % of power requirement during periods of cold weather).

- is supplied to 952 apartment blocks; 3,300 detached/semi-detached/row houses; and 1,141 commercial buildings in Oslo.

- is generated using energy from waste (63.9%), electricity (24.6%) and the heat pumps at Skøyen (7.8%).

- consists of 600 km of pipework and 30 million litres of continually circulating water.

Per Ivar Bergseth and Truls Jemtland from Fortum Oslo Varme.

“My job basically involves checking that everything is working as it should. It requires me to look, smell, and listen. I’m responsible for maintenance too, among other things,” he says.

He tells us about the procedures if a gas or fire alarm is triggered, but as of today’s date, he has never experienced a serious problem with the plant. Over the past 12 months, security of supply has been 99.92 percent.

“The average is around 98-99 percent. The plant may shut down occasionally due to a low flow of sewage,” he says, adding that this only lasts for a few minutes.

“Perhaps we could do with a few more inhabitants, then we’d get a bit more sewage,” he says, laughing.

- Also read: Moves to make a zero-emission Port of Oslo

The possibility that the plant at Skøyen may shut down for a few minutes at a time has little impact on the heat supplied to Oslo’s inhabitants. This is because the district-heating system draws heat from several sources of energy.

A part of the circular economy

Last year, heat from sewage supplied 7.8 percent of the energy for district heating, while 63.9 percent came from waste combustion at waste-to-energy plants. The balance is generated using wood pellets, biogas and bio-oil.

“We exploit resources that already exist, rather than letting them go to waste. This is part of the circular economy, which is good for society and very good for the environment,” says Truls Jemtland.

- Two large heat pumps extract heat from Oslo’s sewage.

- Sewage is used as an energy source to supply heating and hot water to the equivalent of 13,000 apartments consuming on average 10,000 KWh per annum.

- 19 million litres of sewage pass through the district-heating plant each year.

- The heat pumps supply water heated to nearly 90oC to the district heating network.

Operating technician Per Iver Bergseth completes his daily round of inspections faster on a bicycle.

“The sewage pools are on two levels, so that the ‘sludge’ is filtered out. We extract approximately 4-5 degrees of heat from the part of the sewage that is completely liquid,” says Per Ivar.

Emissions from local oil-fired boilers include CO2, NOx and dust, but several of the energy sources for district heating are completely zero-emission.

“The heat we extract is then sent through the heat pumps, which boost the temperature. They work in approximately the same ways as the heat pumps a lot of people have at home. Then we use this heat in the city’s district-heating network,” adds Truls.

Seeking new energy sources for district heating

From 2020 there will be a ban on the use of fossil oil and paraffin to heat residential and commercial buildings. In addition to helping with the phase-out of the use of fossil fuel for heating, district heating also helps improve air quality both indoors and outdoors.

“Emissions from local oil-fired boilers include CO2, NOx and dust, but several of the energy sources for district heating are zero-emission,” says Truls. He also explains that waste-to-energy plants and district-heating plants that run on bio-energy produce only limited emissions. These are strictly monitored at all times, and measures are taken immediately if limits are exceeded.

Truls Jemtland from Fortum Oslo Varme in front of the district-heating plant.

Finnish company Fortum and the City of Oslo each own a 50 percent stake in Fortum Oslo Varme, and Truls is very happy with his company’s partnership with the municipality.

“District heating is a priority for Oslo. The municipality is focusing strongly on area development and environmental work, and good energy solutions are an important part of this,” he says.

- The use of fossil fuels for heating buildings must be phased out by the end of 2020 (when a national bancomes into effect) and replaced with alternative energy sources.

- A general plan for water-borne heating and cooling energy will be completed by 2020.

In addition to a strong commitment to change, he also sees exciting potential for development with several district-heating companies already looking at other possible energy sources.

“For example, we are looking at opportunities to use excess heat from data centres for district heating, and also at ways of storing thermal energy – both during each 24-hour period and throughout the year,” says Truls.