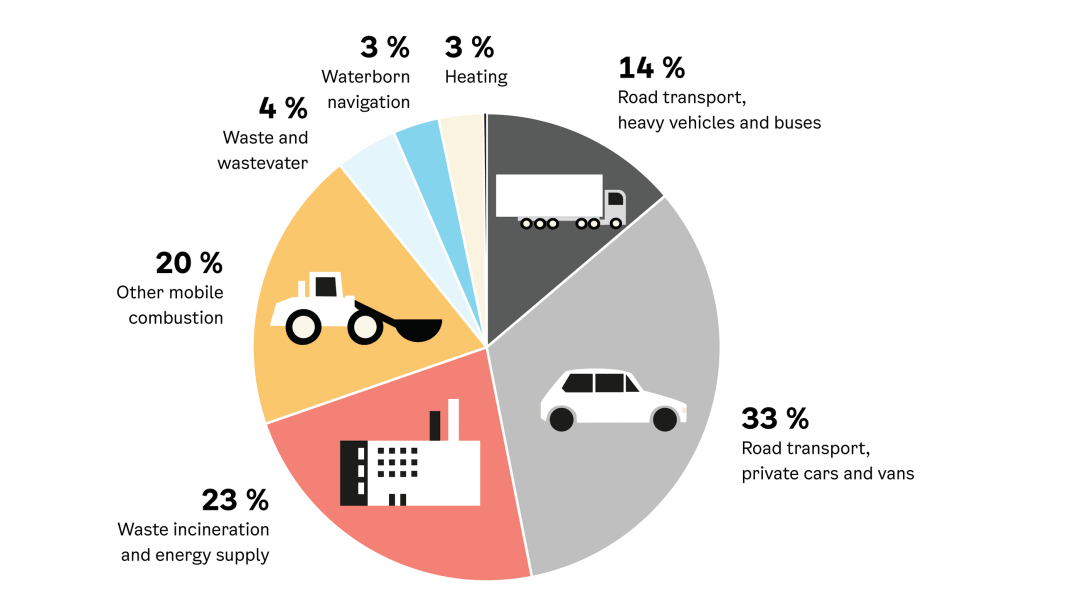

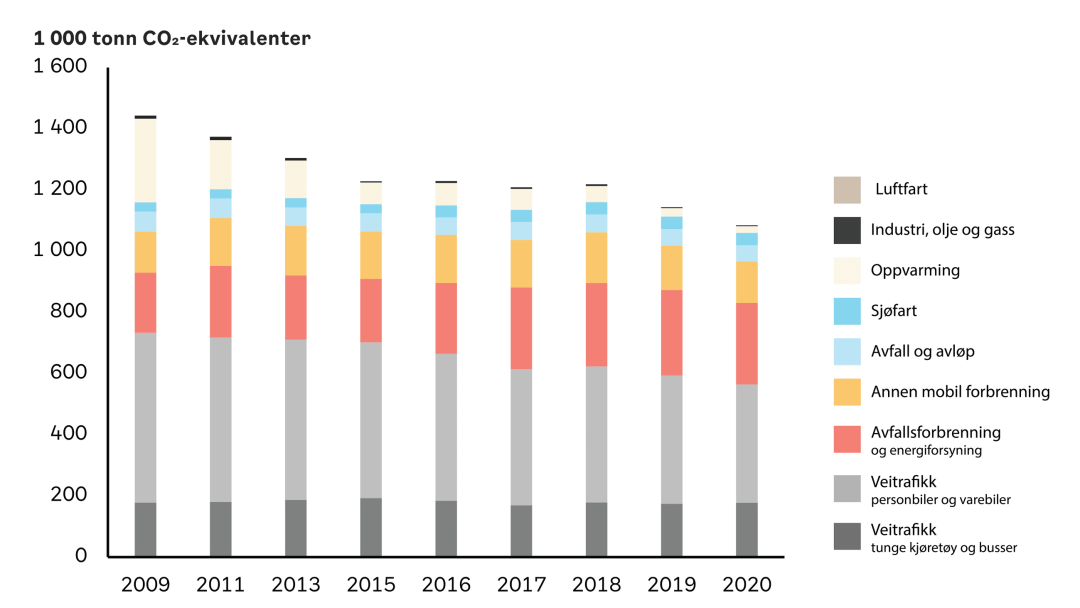

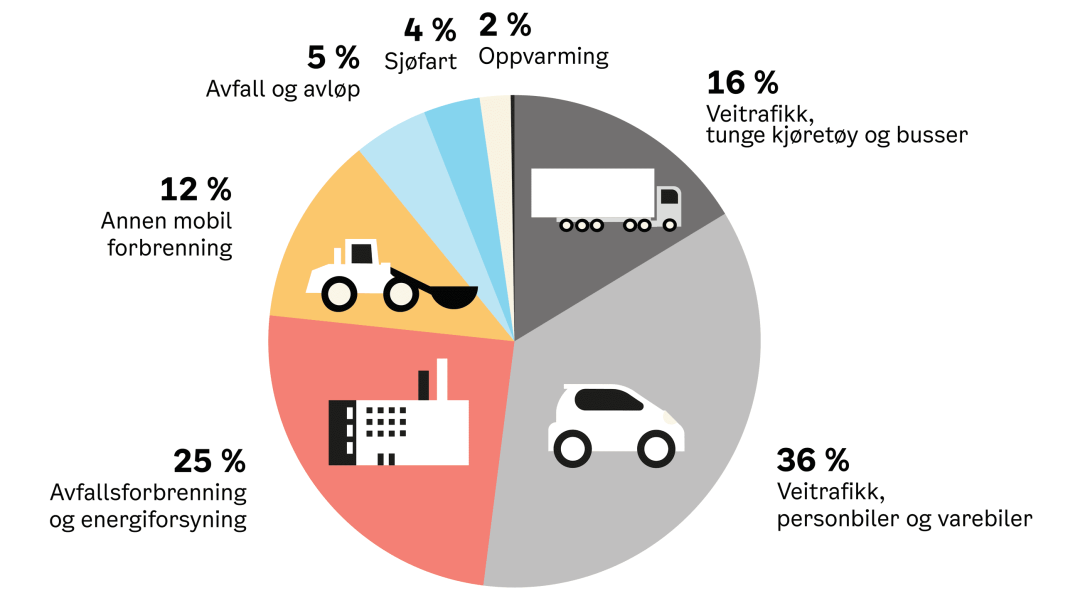

Utslippene fra veitrafikk har hatt en stabil nedgang siden 2009. Dette skyldes i hovedsak økt andel elbiler og økt innblanding av biodrivstoff. Samtidig står veitrafikk fortsatt for over halvparten av de direkte utslippene i Oslo.

Bomringen i Oslo har over lang tid bidratt til å begrense trafikkmengden i byen, i tillegg til å gi insentiv for å velge utslippsfrie biler. Virkemidler som krav i anskaffelser, parkeringstakster, forbeholdte parkeringsplasser og fritak i bomringen for nullutslippskjøretøy har vært viktig for å redusere utslippene fra veitrafikk. Dersom Oslo skal nå klimamålet i 2030, må hele personbilparken og tilnærmet alle tunge kjøretøy som kjører i Oslo være fossilfrie eller utslippsfrie. For å bidra til dette, må virkemidler som stimulerer overgang fra fossile til utslippsfrie kjøretøy og bidrar til å redusere trafikk styrkes.

Overordnete virkemidler

4. Nye takster i bomringen

Våren 2022 ble det framforhandlet og vedtatt nye takster i bomringen (trafikantbetalingssystemet). I tillegg til at takstene i bomringen stimulerer til redusert trafikk og gir insentiv for å bruke nullutslippskjøretøy, går inntektene til å finansiere infrastruktur spesielt for kollektivtrafikk, sykkel og gange. Inntektene vil, med nye takster, øke med 5 mrd. for perioden 2023-2026.

5. Innkjøp av utslipps- og fossilfrie kjøretøy i kommunen

85 % av kommunens egen bilpark er utslippsfri eller går på bærekraftig fornybart drivstoff. En så høy andel er et resultat av Oslo kommunes ambisiøse mål om utslippsfri bilpark. Alle virksomheter i Oslo kommune kjøper inn utslippsfrie kjøretøy (personbiler, varebiler og tunge kjøretøy). Hvis utslippsfrie kjøretøy ikke er et alternativ, skal bærekraftig biodrivstoff (fortrinnsvis biogass) benyttes.

Byrådet setter av 39 mill. i økonomiplanperioden for å kjøpe nye renovasjonsbiler som går på biogass.

6. Etablering av nullutslippssone innenfor bilfritt bylivområdet (utenom Grønland og Tøyen

Byrådet vil innføre en nullutslippssone innenfor bilfritt byliv i sentrum av Oslo fra 2023. En nullutslippssone er en sone der kun el-, hydrogen- og biogasskjøretøy har lov til å kjøre. Dette er et effektivt virkemiddel for å raskt omstille kjøretøyparken i Oslo fra fossil til nullutslipp, og gjennom dette kutte klimagassutslipp fra veitrafikken i Oslo. Ved innføring av sonen, vil det være Bymiljøetaten som har ansvaret for omskilting mm.

Redusert trafikk

7. Insentiver for økt sykling og gange (tilskudd klimavennlige jobbreiser, infrastruktur sykkel, bedre tilrettelegging for gående mm)

Blant de viktigste virkemidlene for å gjøre Oslo til en sykkelby for alle, er et sammenhengende sykkelveinett. Bymiljøetaten drifter, vedlikeholder, oppgraderer, bygger og utvikler ny sykkelinfrastruktur, samt bruker kommunikasjon og kampanjer aktivt for å påvirke reisevaner.

Klimaetaten har flere tilskuddsordninger rettet mot private bedrifter med formål å tilrettelegge for at ansatte skal velge å gå, løpe eller sykle til jobb: Trygg sykkelparkering på jobb, Aktiv til jobb, Vrakpant for parkeringsplass. Her støttes blant annet oppgradering av garderobe, ladestasjoner for el-sykkelbatterier og sykkelvask. Bymiljøetaten har også opprettet en sykkelpilot for bedrifter i Oslo, med formål om å finne effektive løsninger som inspirerer flere til å velge sykkelen til og fra jobb.

Oslo kommune har fra 2022 forsterket innsatsen med å legge til rette for at flere ansatte skal kunne velge en aktiv og klimavennlig jobb- og tjenestereise. Alle virksomheter i Oslo kommune er bedt om å lage planer for hvordan de kan bidra til dette.

Gjennom snarveiprosjektet tilrettelegger Bymiljøetaten for økt gange ved å oppgradere snarveier som gjør det enklere og raskere å forflytte seg som fotgjenger. Prosjektet har så langt resultert i fem oppgraderte snarveier. Nye snarveier skal bygges de kommende årene, i hovedsak rundt t-banenettet.

Byrådet foreslår å sette av 2,5 mill. årlig i 2023 og 2024 for å øke satsingen på trygg sykkelparkering. Videre foreslår byrådet å bevilge 62 mill. til trafikksikkerhetstiltak og 68 mill. til trafikkreduksjon i 2023 og 2024. Dette innebærer tiltak som reduserte fartsgrenser, innsnevringer, fartsdumper og å omdisponere areal fra bil til myke trafikanter og kollektivtransport.

8. Forbedre kollektivtransporten (økt framkommelighet, nye trikker, utbedringer for t-banen mm)

Gjennom mange år med langsiktig og målrettet satsing, har kollektivtilbudet i Oslo blitt et konkurransedyktig alternativ til privatbil. Bruken av kollektivtransporten har imidlertid ikke tatt seg helt opp igjen etter koronapandemien. Byrådet vil derfor forsterke innsatsen for å øke andelen reiser med kollektivtransport, blant annet gjennom lavere kollektivpriser. Utbygging av Fornebubanen, nytt signal- og sikringsanlegg samt oppgradering av Majorstua stasjon slik at stasjonen får større kapasitet, er viktige infrastrukturprosjekter som prioriteres de kommende årene. Innen 2024 skal Ruter sette i drift nye trikker med plass til flere passasjerer.

Bedre framkommelighet for bybussene er en viktig brikke i å styrke kollektivtilbudet. Bymiljøetaten har ansvar for å etablere kollektivfelt, endre områder for parkering og varelevering, bedre skilting, i tillegg til å forbedre framkommeligheten gjennom prosjektet «Kraftfulle fremkommelighetstiltak» som vil videreføres i 2023. På oppdrag fra styringsgruppen til Oslopakke 3, koordinerer Ruter et arbeid med en handlingsplan for framkommelighet i de viktigste transportårene i byen.

Byrådet foreslår å sette av 206,4 mill. i 2023 og 215 mill. resten av årene i økonomiplanperioden for å sikre lavere billettpriser i kollektivtrafikken. Videre foreslås det å sette av ytterligere 72 mill., ut over kommunal deflator, for å dekke kostnadsvekst grunnet ekstraordinær prisstigning i 2023.

9. Økt bruk av deleløsninger (bildeling, el-sykkeldeling mm)

Økt bruk av deleløsninger innebærer at kommunen legger til rette for at innbyggerne har tilgang til mobilitetstilbud som reduserer avhengigheten til å eie egen bil. Dette for å redusere bilbruk og bruk av offentlig veiareal til parkering, samtidig som innbyggerne får frihet til å velge det transportmidlet som til enhver tid passer best.

Bymiljøetaten legger til rette for økt bruk av deleløsninger ved å forbeholde arealer til delebiler, stativer til bysykkelordning og til utleie av elektriske sparkesykler og sykler. Bymiljøetaten gjennomfører en prøveordning der 600 offentlige parkeringsplasser har blitt forbeholdt bildeling. Byrådet vil reservere ytterligere 400 parkeringsplasser til bildeling. Byrådet vurderer også løsninger for å øke elbilandelen blant bildelingsbilene.

Ruter ser på hvordan tilbud av bysykkel, elektriske sparkesykler og andre former for delemobilitet kan integreres i Ruter-appen for å muliggjøre en sømløs reise med ulike former for transportmidler. Ruter har flere piloter med delemobilitet som formål, hvor innbyggerne får tilgang til delebiler, elektriske lastesykler og andre relevante tjenester, som sykkelverksted. Ruter planlegger også piloter med delte selvkjørende kjøretøy, samt samkjøring av passasjerer og gods.

10. Parkeringsvirkemidler (fjerning av parkeringsplasser, økte takster, ny parkeringsnorm, beboerparkering)

Kommunen prioriterer framkommelighet for blant annet sykkel og kollektivtrafikk over parkering for bil og omprioriterer gategrunn fra parkering til andre formål. Siden 2015 har kommunen fjernet over 6000 parkeringsplasser. I tillegg har byrådet de siste årene økt parkeringstakster for å redusere bilbruk. I 2023 vil byrådet sette takstene i indre by opp, blant annet fordi det der er et svært godt kollektivtilbud. Takstene settes ned i ytre by. Se en mer detaljert omtale av takstene i MOS-sektoromtale.

Kommunen har også innført beboerparkering, en ordning der beboere får bedre tilgang på og reduserte årspriser for parkering i sitt område, mens besøkende må betale avgift pr time. Dette bidrar til mindre fremmedparkering i beboerområdene og mer forutsigbar parkering for dem som bor i området.

Byrådet har lagt frem forslag til nye parkeringsnormer som skal behandles i bystyret i 2022. Normene skal være veiledende for fastsettelse av parkeringsdekning for bil og sykkel i nye reguleringsplaner. I den nye parkeringsnormen er minimumsgrense for antall parkeringsplasser erstattet med en maksimumsgrense. I tillegg stilles det krav til lademuligheter på minst 50 % av parkeringsplassene, og det er krav til antall og kvalitet på sykkelparkeringer. Opp mot 10 % av parkeringsplassene i større parkeringsanlegg bør vurderes avsatt til bildeling og i reguleringsplaner skal det ses på mulighet for sambruk.

Kommunens virksomheter er i 2022 bedt om å vurdere om parkeringsplasser ved tjenestestedene kan fjernes og/eller om det er relevant å etablere lademuligheter.

11. Redusert transport av masser og avfall

Kommunen jobber aktivt for å redusere transport av masser og avfall fra bygge- og anleggsplasser i Oslo ved å øke gjenbruk av masser i kommunale prosjekter eller internt i byen. Utviklings- og kompetanseetaten jobber for å øke kunnskapen blant Oslo kommunes innkjøpere av massetransporttjenester om hvordan masser kan gjenbrukes.

I den tverretatlige kommunale arbeidsgruppen, bestående av Plan- og bygningsetaten, Klimaetaten, Oslobygg Oslo KF, Oslo Havn KF, Bymiljøetaten, Vann- og avløpsetaten, Bymiljøetaten og Fornebubanen, og prosjektet Pådriv i Hovinbyen, utforskes nye løsninger og logistikk for massehåndtering. Eiendoms- og byfornyelsesetaten fremskaffer arealer til massehåndtering på bestilling fra relevante kommunale virksomheter.

Plan- og bygningsetaten ber forslagsstiller i alle nye plansaker hvor det er relevant, om å redegjøre for spørsmål knyttet til massehåndtering. Klimaetaten og Plan- og bygningsetaten jobber med å fremskaffe arealer til lokal massehåndtering gjennom planprosesser, i tillegg til å utrede handlingsrom for å sikre at det settes av arealer til massehåndtering. Plan- og bygningsetaten har opprettet en toårig stilling for en massekoordinator som startet 01.09.2022.

Fornebubanen reduserer transport av masser i sine prosjekter ved å stille krav til at entreprenørene tar klimavennlige valg ved levering av avfall og masser. Entreprenørene måles blant annet på kilometer transport for å skape bevissthet rundt antall kjøretøy, og det benyttes lokale mottak for masser der det er mulig.

Utslippsfrie personbiler

12. Etablere ladeinfrastruktur for personbiler

Et godt tilbud av ladeinfrastruktur er avgjørende for å elektrifisere transportsektoren, og for en vellykket innføring av andre virkemidler som for eksempel nullutslippssoner, klimakrav til taxinæringen og klimakrav i anskaffelser. Bymiljøetaten skal etablere 150 ordinære ladepunkter og sørge for kommunal involvering i 10 hurtig- og lynladere i byen i 2023.

Gjennom Klima- og energifondet gir kommunen tilskudd til ladeplasser for elbil i borettslag og sameier. Ordningen er viktig for å gi mulighet for overgang til elbil for alle som trenger tilgang til bil, også de som bor i borettslag og sameier. Siden tilskuddsordningens oppstart i 2017 er det utbetalt om lag 80 mill. som har muliggjort nesten 55 000 ladeplasser.

13. Insentiver for utslippsfrie drosjer fra november 2024 (krav, tilskudd, ladeinfrastruktur mm)

Kommunen bidrar til å tilrettelegge for at alle drosjer som kjører i Oslo, skal være utslippsfrie innen november 2024, etter forskrift om miljøkrav for drosjetransport i Oslo. Bymiljøetaten skal i 2023 etablere 12 nye ladepunkter forbeholdt drosjer, gjennomføre piloter for hurtiglading og tilrettelegge for at utslippsfrie drosjer er prioritert på drosjeholdeplasser. Gjennom Klima- og energifondet gis det tilskudd til hjemmelading for drosjesjåfører.

Utslippsfrie varebiler

14. Krav til utslippsfri varelevering på oppdrag for kommunen

Kommunen stiller krav til at alle varer og tjenester som leveres til Oslo kommune transporteres med klimavennlig drivstoff. Krav til kjøretøy og drivstoff skal enten settes som et minimumskrav eller som et tildelingskriterium i anskaffelser. Kravstillingen gjelder også driftskontrakter. I anskaffelsene blir leverandørenes andel av utslippsfrie og/eller kjøretøy på biodrivstoff (fortrinnsvis biogass) vektlagt.

Alle etater er ansvarlig for å bruke Oslo kommunes standard klima- og miljøkrav til transport i anskaffelser av varer og tjenester. Det stilles også klima- og miljøkrav til transport i kommunens kontrakter innenfor bygg- og anlegg. Byrådet har strammet inn kravene, slik at alle samkjøpsavtaler stiller krav til/premierer transport av varer og tjenester med nullutslipp/biogass. Dette arbeidet vil fortsette i 2023.

15. Insentiver for utslippsfrie varebiler (etablere/tilskudd til ladeinfrastruktur, samlastsentre, lastelommer parkering mm)

Oslo kommune legger til rette for bruk av utslippsfrie varebiler ved at Bymiljøetaten etablerer ladeinfrastruktur og prioriterer parkeringsplasser til elektriske vare- og nyttekjøretøy. Når de 15 gjenværende næringsparkeringsplassene skiltes om til å forbeholdes elektriske varebiler i 2023, vil alle næringsparkeringsplasser i sentrum være forbeholdt elektriske varebiler. Elektriske varebiler passerer gratis i bomringen og står gratis i beboerparkeringsområdene. Eiendoms- og byfornyelsesetaten har i oppdrag å fremskaffe arealer til samlastsentraler etter bestilling.

Bymiljøetaten tilrettelegger for omlasting av varer på Filipstad ved å sikre tilgang på strøm og ladepunkter på de tre bylogistikkterminalene. Dette reduserer utslipp ved at Posten, DHL og Schenker laster om til elektriske varebiler og benytter disse til levering i siste ledd av transporten.

Gjennom Klima- og energifondet gir kommunen støtte til ladeinfrastruktur hos bedrifter og hurtigladere for elektriske varebiler.

Utslippsfri/biogass busser

16. Bruk av utslippsfrie busser i kollektivtrafikken

Ruter har inngått nye busskontrakter som innebærer at alle busser innenfor Oslo blir elektriske innen utgangen av 2023, med unntak av busslinjen over Ulvøybrua som ikke tåler vekten av en elektrisk buss. Dermed vil all kollektivtrafikk i Oslo på land være utslippsfri, da t-bane og trikk allerede er elektrisk.

17. Anskaffelse av utslippsfri tilrettelagt transport

Ruter har inngått en ny kontrakt som viderefører bruk av biogass og elektriske spesialbiler (i stor grad minibusser) for den tilrettelagte transporten (TT-tjenester) i Oslo. Tilrettelagt transport er et tilbud for dem som ikke har mulighet til å benytte ordinær kollektivtransport.

18. Insentiver for utslippsfrie tur- og ekspressbusser (etablere/tilskudd til ladeinfrastruktur)

Oslo stiller krav i anskaffelser om at bussene som kjører på oppdrag for kommunen er utslippsfrie. Det brukes allerede elektriske turbusser til skoleskyss, og flere selskaper har anskaffet elektriske busser for å kunne kjøre på oppdrag for Oslo kommune.

Klimaetaten gir tilskudd til ladere for lastebil og buss gjennom Klima- og energifondet. Bymiljøetaten etablerer offentlig tilgjengelige hurtigladere tilrettelagt for tunge kjøretøy.

Biogassfritak i bomringen og forutsigbarhetsvedtak for at tunge kjøretøy på nullutslipp og biogass har avgiftsfritak i bomringen til ut 2027, reduserer risikoen ved å investere i utslippsfrie busser for selskaper som kjører mye i Oslo.

Utslippsfri/biogass lastebiler

19. Krav til bruk av utslippsfrie lastebiler på oppdrag for kommunen

Kommunen stiller krav i anskaffelser om at alle kjøretøy som benyttes til transport i forbindelse med leveranse av varer eller tjenester til Oslo kommune (inkludert bygg og anlegg), leveres med elektrisitet, hydrogen eller biogass. Fra 2025 vil dette gjelde som standardkrav. Kravet har vært viktig for å få i gang markedet for utslippsfri tungtransport.

Fra 2020 har Oslo kommune stilt krav om fossilfri transport av masser til og fra byggeplass i egne prosjekter. I tillegg brukes tildelingskriterier for å fremme bruk av elektrisitet, hydrogen og biogass, i tillegg til å kjøre så korte distanser som mulig. Alle relevante virksomheter stiller krav i nye kontrakter der det er aktuelt.

20. Insentiver for utslippsfri tungtransport i Oslo (fritak i bomringen, tilgang i kollektivfeltet, etablere/tilskudd til ladeinfrastruktur, fremskaffe arealer til energistasjoner mm)

Virkemidlene for utslippsfri tungtransport skal redusere utslipp fra lastebiler i Oslo ved å forsere overgangen fra diesel til el, hydrogen eller biogass. Bymiljøetaten skal legge til rette for 20 nye ladepunkter tilrettelagt for vare- og nyttetransport i 2023

Klimaetaten og Eiendoms- og byfornyelsesetaten jobber for å legge til rette for energistasjoner som tilbyr lading og fylling av fornybare drivstoff, slik som biogass, hydrogen og hurtiglading. Gjennom Klima- og energifondet er det etablert tilskuddsordninger for hurtigladestasjoner for tunge kjøretøy og biogassfyllestasjoner. Formålet med ordningene er å sikre et tilstrekkelig tilbud av lade- og fyllemuligheter i byen. Ordningene kommer i tillegg til eksisterende tilskuddsordning for etablering av lading på eget område for bedrifter. I 2022 ble det bestemt at biogasslastebiler ikke skal betale i bomringen, sammen med et forutsigbarhetsvedtak om fritak fra takst minimum til 2027. Oslo kommune vurderer sammen med Statens Vegvesen hvordan kollektivfeltene kan innrettes slik at de fremmer trafikk- og klimagassreduksjon, blant annet vurderes om elektriske lastebiler eller lastebiler som går på biogass skal få kjøre i kollektivfeltet.

Klimaetaten har fått midler fra Klimasats til å videreføre arbeidet med å gjøre Oslo til en foregangsby for utslippsfri tungtransport. En viktig del av dette arbeidet er å ha god dialog med næringslivet gjennom blant annet nettverkene slik som Næring for klima og Grønt landtransportprogram.